Scientists discover 'electron equivalents' in colloidal systems

Atoms have a positively charged center surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged particles. This type of arrangement, it turns out, can also occur at a more macroscopic level, giving new insights into the nature of how materials form and interact.

In a new study from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory, scientists have examined the internal structure of a material called a colloidal crystal, which consists of a highly ordered array of larger and smaller particles interspersed in regular arrangements. A greater knowledge of how colloidal crystals are structured and behave could help scientists determine the applications to which they are best suited, like photonics.

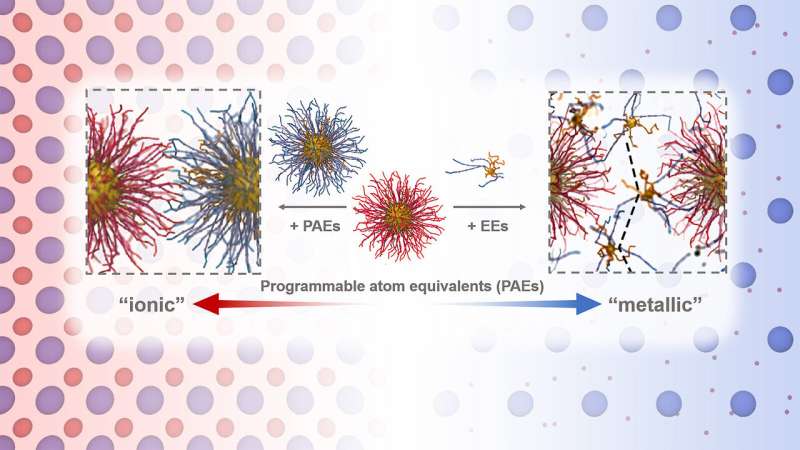

In pioneering research outlined in a recent issue of Science, scientists tethered smaller particles to larger ones using DNA, allowing them to determine how the smaller particles filled in the regions surrounding the larger ones. When using particles as small as 1.4 nanometers—extremely small for colloidal particles—scientists observed an exciting effect: The small particles roamed around regularly ordered larger particles instead of remaining locked in an ordered fashion.

Because of this behavior, the colloidal crystals could be designed to lead to a variety of new technologies in the field of optics, catalysis, and drug delivery. The small particles have the potential to act as messengers, carrying other molecules, electric current or information from one end of a crystal to another.

"The smaller particles essentially act like a glue that holds the larger particle arrangement together," said Argonne X-ray physicist and study author Byeongdu Lee. "With only a few beads of glue, the best position to place them is on the corners between the larger particles. If you add more glue beads, they would overflow to the edges."

The small particles that sit on the corners tend to stay still—a configuration Lee called localization. The additional particles that are on the edges have more freedom of movement, becoming delocalized. By being tethered to larger particles and with the ability to be both localized and delocalized, the small particles act as "electron equivalents" in the crystal structure. The delocalization of small particles, which the authors called metallicity, had not been observed so far in colloidal particle assemblies.

Additionally, since the small particles delocalize in part, the effect creates a material that challenges most traditional definitions of a crystal, according to Lee.

"Normally, when you change the composition of a crystal, the structure changes as well," he said. "Here, you can have a material that is able to maintain its overall structure with different proportions of its components."

To image the structure of the colloidal crystals, Lee and his colleagues used the high-brightness X-ray beams provided by Argonne's Advanced Photon Source (APS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility. The APS offered a key advantage in that it allowed the scientists to observe the structure of the crystal directly in solution. "This system is only stable in solution, once it dries, the structure deforms," Lee said.

More information: Martin Girard et al, Particle analogs of electrons in colloidal crystals, Science (2019). DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw8237

Journal information: Science

Provided by Argonne National Laboratory